In her exhibition Higher Ground (Jan. 28-Mar. 12, 2017 at The Compound Gallery), Jeanne Lorenz explores water, fire, climate change, high-altitude hiking hazards, the history of textiles as pattern and protection, and the intersections of environment and social justice. The show took root in 2015 during her 2,000-mile trek on the Pacific Crest Trail with her husband Canyon and their daughter Adeline, then age 10.

Here Jeanne walks us through the evolution of the project, from the tiny sketchbooks she filled during the months on the trail, through paintings, collages, and wall-size installations. In this ongoing explorations Jeanne uses the immediate, sensory experience of living in the elements to explore perceptions of familiarity, danger, and interrelationship. We were joined in our talk by Compound artist Takehito Etani and Compound co-manager Matt Reynoso.

Articiple: I’d like to start by getting the bigger context of the work in Higher Ground. I know this came out of your hike on the Pacific Crest Tail (PCT) in 2015, and you’ve been addressing that in a lot of different ways. It’s also related to the other large-scale installations you’ve done over the past few years, so maybe we can weave back and forth between those ideas. Do you want to start with the drawings you did on the trail?

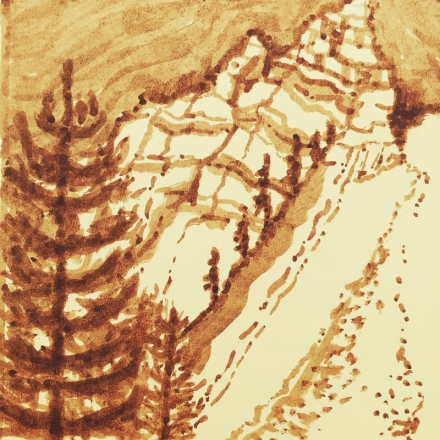

Looking out on the desert from the Acorn trail, 2015

Ink drawing, detail from sketchbook

Original: 5 x 3 inches

Jeanne: I had a sabbatical that year. I knew I wanted to take this long walk, and some artist friends said, “What are you doing, you should really be spending the year making work!” I felt like going out on the trail with one tool would divorce me from the computer in a way that I felt like I really needed to do. A lot of the work I’d been doing was very digital. And now it’s not really digital at all. It’s mostly just about looking at things in nature and trying to make patterns from them. That’s what a lot of this installation is.

Articiple: It looks like you filled a sketchbook on the trail almost every few weeks.

Jeanne: I did a lot of drawing, and I continue to draw. I still draw in this format. But then I also allowed myself to get bigger. So this is my big-sized sketchbook (7 x 10 inches). Now I’m realizing that this is a size I would feel comfortable actually showing. If I ever decide to show my sketchbook drawings, I’ll show them as drawings and not just as sketchbooks.

Articiple: You can take them out and treat them as finished works. So, was there an evolution while you were on the trail, of how you wanted to deal with the material constraint and the size and so on?

Jeanne: Definitely. I stuck with the same sketchbook and the same pen the entire time and I developed a really strong connection to it. So I stayed with the same material and the mechanism. In the beginning I was trying more to be very literal with the drawing. Later, I would just start drawing and it would become something more like the way I would paint, where you’re responding, you’re making decisions in the process of making the drawing. And also I let myself go back and work into them. The nice thing is, this ink is very transparent so it lends itself to being built up. Sometimes I’ll go back and darken things that need to be darkened.

Articiple: Did you send the notebooks home from the trail as you filled them?

Jeanne: I would mail them. At one point I gave a couple to my mother-in-law, and then when I returned she said she didn’t have them. I was a little like, oh, no. And then, it was amazing, because I opened up a drawer in my house and there they were. So she had brought them home to me. But mostly I would mail things home. And I did not lose a single package. It was really great. And I would mail myself ink. All I needed was to refill my pen, and I carried a small amount with me. But I would replenish that supply when we got our food drops.

I’m just going to keep working this way, I think. This weekend I’m going out to a farm near Redding, and I’m going to draw there. It’s great to be in the landscape thinking about environmental issues.

Articiple: So how did that come up on the trail? Obviously you’re in this remote area without many signs of development or industry, sort of ‘unspoiled nature’. But still, there are signs of humans wherever you go.

Jeanne: The main thing for us was water. It was a huge issue. Right now it’s so wet and everything is so mossy. But the PCT was experiencing the worst drought in 150 years the year we chose to hike it. It was really intense getting ready, figuring out how we were going to handle it. At points we walked across basins 42 miles long without any water. That was a real challenge. Often we would think, what are we doing, bringing our child into this?

Post-trail, I read a lot of post-apocalyptic environmental fiction. My favorite was called Gold Fame Citrus by Claire Vaye Watkins. The title is about all the things that people come to California for. It’s set in the California drought. It hit home for me.

I’m happy that it’s raining now but I also know that we’re still having huge water issues. It’s something that our state and our country will continue to face. Where I live [in Canyon, CA], there’s a plan afoot to pave and develop 140 acres of watershed. So this is something that I feel very strongly about. I can’t allow this to happen. It’s the first time where I feel like I may be ready for some direct action if it came down to that. I feel so emotional about it.

I’m trying to document these frogs that are down in this watershed, and finding out about the plants, reading about moss, trying to know as much as I can. And also trying to connect to the environmentalist groups that already exist, that have been waging the battle for a long time.

Articiple: Was there an environmental impact report for that project?

Jeanne: Not yet. The proposal is in the planning stages. The planners are telling us, “Calm down, it’s not a big deal.” But when you see the plans it’s so horrifying.

Articiple: I worked for a while with an environmental restoration firm. Most of the staff were wildlife biologists. It was their job to do population surveys of whatever protected species were in the development area, the California red-legged frogs and such, and design corridors or protected areas for them. Anytime a development impacts a species with state or federal protection, the developer has to hire a firm like that to make sure the protections are enforced.

Jeanne: I want to see the red-legged frogs. I’ve only seen the chorus frogs, the tree frogs.

At the other end of Canyon there’s a park. We’re happy that the land was acquired by a park. They’re daylighting the creek. They also have a plan to make a campground. We’re not super happy about that, but suddenly this new development is much more threatening. So our energy has shifted.

Articiple: Right. You’ve got to stop the biggest threat first.

What came after the sketchbooks in this project?

Jeanne: I was really lucky because when we hiked the PCT I was on sabbatical. When we came back I was able to go on my first residency, to the Vermont Studio Center. I would highly recommend it to any artist. They’re the largest residency program, maybe in the world. It’s truly international. They do a really good job at making it diverse, especially in terms of age. So any person can go there and feel comfortable and be a part of that community.

I had never experienced a month-long residency. The fact that I could go into a studio every day really allowed me to go through these drawings and think about them. I made a lot of really bad work during that month. A very good friend of mine is a wonderful painter who works with landscape. She was a visiting artist during that time. So I was able to have a studio visit with her. I felt like the work that I had been making was mildly horrifying. But after we met, I turned a corner and was able to really narrow the focus and start making some of the work that’s in this show.

I wanted very much to do an intervention on a building there. I identified the old Johnson Woolen Mills building. I wanted to talk about water and wool as a collaboration between the things that can kill us and the things that can keep us alive.

Articiple: And ways that we interact with the environment, using it to produce things we use.

Jeanne: And all the beautiful patterns that come out of weaving wool. So this [freestanding wall installation] started out as an installation there. I realized that I would be crazy to want to wheatpaste a building in Vermont in December. It was really cold, and they kind of talked me down from it. But I did a photographic rendition of what I wanted it to look like. And that actually really helped me come to this installation.

It was also interesting there because—they serve very healthy food so you really don’t want to miss meals and you want to go hang out with the other artists. So I was getting up early, going to my studio and then going to lunch. One day, I had painted a section of this on the floor. When I came back from lunch, there was all this mark-making that I hadn’t done. It was the salt from the floor from this old normal school that my studio was in, just coming up through the floor and affecting the water-based medium I was using. So now I have been using some salt in my process, and I definitely want to check that out again.

All these little flock marks are just coming out of the floor.

Articiple: Amazing. So this was acrylic medium that you mixed with pigment?

Jeanne: Yes. I was making my own paint. I was trying to use a limited palette that would reference the trail drawings. For years I’ve been using Guerra paints, a company in New York. They seem to be the only company that grinds pigment into water, so it’s a dispersion that you can make acrylic with. These are all different cocktails of acrylic that I made. Pretty much everything is acrylic, except for the drawings.

Wool and Water study, 2017

Homemade walnut ink and Noodler’s kiowa pecan ink on Crane Lettra ecru paper

I made walnut ink with my students from trees on the Solano campus. I’m in the process of making iron gall ink. It’s not ready cause it takes a long time to ferment. It’s funky. I have some vats of it sitting in my office.

Articiple: And that will be a red?

Jeanne: I think it’s actually very black. I haven’t figured out how to make the red iron pigment. Where I live, there’s an iron-loving microorganism in the water. My water is actually the color of that wall, the orange part, if you get down to the bottom of the tank. It runs really red. People keep telling me I should go up to our water system and harvest some of the residue. I think it’s probably just iron in the water, and the microorganism is gone. I think if you dried it out, you could use it. It would be clotted, but the walnut ink is also like that.

Take: How did you make the walnut ink?

Jeanne: There are a lot of walnut trees where I teach. It’s the outer husk of the walnut that you use. Some of them we picked from the trees, some of them we picked up off the ground. We peeled off the spongy outer part and soaked it in water for a week. It became very black and very funky. Then I strained it through cheesecloth. And I made a watercolor medium that had glycerin, ox gall, and some honey. It’s not really ink, it’s more like watercolor. But it works really well. You can get different tonal ranges.

Articiple: Right. You’ve got everything from really dense, dark areas to transparent washes.

Take: So honey is the binding agent?

Jeanne: Honey is an anti-microbial.

Articiple: So it keeps it from fermenting more.

Jeanne: It also allows you to reconstitute it. If you have it on your palette, it dries shiny. But if you mist it with water, it becomes fluid again. I think usually there’s some kind of sugar in watercolor. Or gum arabic. You can see here, it got shiny. A couple of these drawings were so sticky that they stuck together and I had to repair them.

So I’m in love with drawing. I feel like it took me this long to figure out how to draw.

Articiple: There’s a lot of really nice varied line quality in these.

Jeanne: Just today I made a monoprint. I feel like if you have a daily drawing practice you already have a mechanism going that helps you move through imagery in a way that’s a little bit less self-loathing. You’re like, “I’m just going to start it. I’m not going to worry about it.” There will be less anxiety. It will just be like, “Here we go.” I feel like I needed that.

Articiple: Right. Then it’s more like a practice than a high-pressure goal.

It looks like you just used a pen nib and brushes?

Jeanne: It’s a Japanese tool, a Kuratake. It’s a fountain pen that has a sable tip. I converted it so I can use the ink of my choice. It comes with black, with cartridges that you can throw in. But once you convert it, there’s no waste. Whenever you need ink, you just create a vacuum and suck the ink up. I’ve had this pen for four years. The pen will never go away. The sable tip gets worn down. So you can see in some drawings, at the beginning they’ll be sharp and fine and lean, and then suddenly you wear it down and it’s harder to make fine lines. Right now I’m carrying around an extra tip, waiting to replace the old one. But I don’t want to replace the old one because I like what it’s doing.

Articiple: It’s amazing that these are all with the same tool.

Jeanne: The washes are not done with the same tool. I try to start with the tool. You can do a lot of inking and filling. But because these are not my sketchbook drawings, I go in and layer things afterwards, if it needs depth or something.

I’m fairly religious in the sketchbook practice, where it’s just the pen. That’s why it has to be small. But then it’s underwhelming, because when you show somebody, you’re like, “Look at my little iphone-sized drawing!”

Articiple: It’s like a miniature.

Jeanne: But it’s not the level of detail of a miniature. To me they feel more loose and painterly. I’m very happy with them. But when I talked to Matt and Lena about having a show here, it took me a long time to figure out what I wanted to do. I didn’t want to show the sketchbooks because it was like, “Here are these tiny things!” Not super exciting. So the vitrine was a great way to display the sketchbooks. It’s so great that they had that.

Articiple: It’s a really important part of this show. It’s what all the other work came out of.

Did you do these fabric-based patterns while you were in Vermont?

Jeanne: Yeah. I was researching the Johnson Woolen Mill. I’ve had so many different jobs in my life. One of them was, I spent a couple years restoring antique Persian carpets. During that time I learned a lot about the patterns of the Caucasus and how they inspired so many patterns. A lot of Navajo rug patterns come from Caucasus rugs—not all of them, but some of the later ones. Settlers would go to a weaver and say, “I can’t afford a rug from the Caucasus, but I would like you to make me this.” So some of the patterns that we would identify as Native American actually go back further.

Articiple: I’ve been working with Islamic tile patterns. It’s the same, they’re related to Persia and the Caucasus.

Jeanne: The Fertile Crescent!

Articiple: Right. A lot of trading and exchange of ideas going on.

Jeanne: And in Japan, they’ve got the ikat woven pattern, for clothing that farmers wear, the black and turquoise. This one is a little bit like that.

Articiple: Ikat fabric, that’s when they pre-dye the pattern into the fiber before they weave it, right? It’s unbelievable how much precision and planning that must take.

Jeanne: Things were going a lot slower.

Articiple: Right. We do the same level of detail work now, we just use a lot of automation to do it.

Jeanne: They didn’t have machines, that was the only way. They didn’t really think about “time equals money”.

Articiple: Right. They weren’t “wasting” time, they were using it.

So when you made these patterns, did you find them online?

Jeanne: The Vermont Studio Center has an amazing library, so I found some things there. Then I also visited the Johnson Woolen Mill. This big, quasi-abandoned factory was between where I was living and where my studio was, so I was constantly going by it. I went in and checked it out. I really thought about how they’re essentially in the business of selling nostalgia to people who want a taste of this time in Vermont when things were hand-crafted. You want this heirloom, very expensive wool jacket that maybe you’re going to hunt in but maybe not. The other thing I found out that was super cool was that the icemen who were harvesting ice from these lakes in New England had a specific kind of pant that the Johnson Woolen Mill made. They were these green icemen pants.

Articiple: So they wouldn’t get cold.

Jeanne: Yeah. If you’re dealing with ice you have to protect yourself from water. Wool is great because it repels water. A lot of people on the PCT were proselytizing about their wool clothing.

Articiple: Instead of Goretex or something engineered.

Jeanne: Right. No synthetics, just wool, because it’s super warm, it’s also cool, it’s a little less stinky.

Take: It’s anti-microbial.

Jeanne: Yeah. But now there are all these Teflon-fiber anti-microbial fabrics.

Articiple: But they’re all trying to replicate natural materials.

Jeanne: The other thing I’ll say is that the Johnson Woolen Mill slyly mixes nylon in with their wool now.

Articiple: To make it more durable?

Jeanne: Yeah. It’s supposed to be a little stronger.

But when we were hiking, water was what it was about. It was either lack of water or too much water. We’re feeling like we’re going to die in a hailstorm because we’re being pummeled and we don’t have shelter, or we’re going through a place where there are absolutely no seasonal streams and we can’t carry enough water.

Articiple: What happens when there are days where you can’t carry enough?

Jeanne: At one point we hired a guy to come out to the PCT in the middle of the desert and drop water for us. There were quite a few water caches, but you’re never supposed to rely on a water cache.

Take: What is a water cache?

Jeanne: People go out and put gallons of water near the trail for the hikers. It’s sort of like we’re human hummingbirds. They’re like, “Oh, you’re so beautiful and wonderful. Look at you on your awesome pilgrimage across the country. We’re going to bring water to you.” It’s beautiful. But you can’t really rely that the water will be there. In one case, we got to a place that had an amazing water cache. We took water from it, and then within 12 hours a flash flood had completely washed the whole thing out. The vehicles that were coming through to replenish it couldn’t get through anymore.

The guy who was replenishing it, his trail name is Devil Fish, he showed a video to me of the flood. It was as if the desert floor was up to your waist, roiling like some molten lava. It was just like that, snap, the water just comes through.

Articiple: It can’t soak in anywhere because the ground is so hard.

Jeanne: It just goes so fast. It was nuts. But Jugs was this kid that we paid to bring us water.

Take: How did you find the kid?

Jeanne: It was as if we had been kidnapped. We were at the Tehachapi post office waiting to get Adeline a pair of shoes that we had ordered. The shoes didn’t come and we were really bummed and Canyon was very stressed. This woman walked in. She knew about us because we were hiking with a kid and it was unusual. She very much wanted to give us a ride. So we decided, yeah, we’ll just get in this woman’s car and she’ll take us wherever. We ended up going to the Mojave Motel 6, which is quite a scene. In Tehachapi we stayed in a nicer hotel, thinking, we need a break, we just want to chill out. The Motel 6 was way more fun. It was where everyone from the trail was. There was a swimming pool. People were barbecuing. It was just a convergence. It’s a big part of the PCT because you’re almost at the top of the desert when you get there, so you’ve really endured a lot. You’re about to get to Kennedy Meadows South, which is like—if you think about the Heironymous Bosch painting, The Garden of Earthly Delights, everyone thinks it’s going to be like that.

Articiple: People must think, it’s called ‘meadow’, it must be lush!

Jeanne: Right, it’s a meadow. It’s where you get your big resupply before you enter the Sierra. It’s where you know you’re done with the desert and you’re going to be going into the mountains. All hell does break loose there, so that’s kind of great. When we hiked in it was dark and we had two little kids with us. We had Adeline and her cousin Julia. We could see in the distance that there was an enormous tipi and there was fire and people were whooping and hollering. When we got close enough for them to recognize that there were people arriving, everybody started whooping and screaming hysterically and clapping. Canyon turned to me and said, “I don’t know what kind of party we’re coming into.” But it turns out they just have a tradition of clapping everybody in because you made it that far. It was sweet, but we didn’t realize that until the next morning. The other thing is, they remove the spigots from the water. So by the time we got there, it was dark, it was crazy, the store was closed, there was nothing we could offer the children, and there was no water. So I had to go around and ask. Finally I ran into a hiker I knew and she gave me water.

They have to do it. Their water system is so fragile that they can’t have people just leaving it on. I think they’re trucking it in.

I’m still obsessed with water. Now, living on a watershed and thinking about what that means, trying to protect it, it’s become my issue. But there are so many social issues. They existed always, but now we’re in a place where everyone is more aware.

Articiple: And with water or any environmental issue, we know it’s always low-income people who are disproportionately affected.

Is this wall piece related to the work in your solo show at Solano last year? (Force of Nature, Herger Gallery, Solano Community College, March 2016)

Jeanne: Yes. This is somewhat new. The configuration is new and the patterns are new. The trees I made at Solano based on trees I had done in Vermont. So I’m still trying to deal with these ideas. Some of it is, you know how you have an idea and you’re trying to work through it and you feel like you’ve done it but it hasn’t been successful the way you want it to be. I feel like I’m still trying to deal with how the desert looked specific to charred fire and burnt trees. I haven’t gotten there yet. We had some amazing visual experiences, trees that would be upright, completely blown upside down and stuck into the ground, where we would have to climb through them. You just wonder, how did this happen, this is so unusual. Or, in a completely black and charred forest, there’s an amazing sense of renewal, with beautiful wildflowers just bursting up.

I finally saw my dream flower, a Matilija poppy, in the wild. For years I’ve know that they’re supposed to only grow after fire. I have them on my property and I love them. To see them in the wild was like, whoa! Because it was a charred, burnt area, but there were these big, beautiful white poppies. That was cool.

But there are also a lot of invasive species. And you’re like, we’re too far out for this to be here!

Articiple: Like broom and fennel?

Jeanne: Worse. Like star thistle. And you know it’s probably coming from horses. I saw some stuff pretty high up in the Sierra, where it didn’t seem like it should be there.

The David Brower Center hosted an amazing talk about this new textbook called Ecosystems of California. It’s a 1,000-page book that talks about California. It’s the first California ecology textbook in a long time. The guy who is the chief editor is Harold Mooney, from Stanford. He talked a lot about his scholarship, which was going out into the back country and seeing these stands of trees that were from much further away, and wondering what was happening. So he was the first person to document climate change out in the wilderness.

Articiple: So no matter how far you go into the wilderness, you can find evidence of change.

Jeanne: We definitely saw that. We saw the diminishing snowpack over a series of summers. We hiked the Sierra three summers in a row.

Articiple: It must be coming back this year finally, with the rains we’ve had.

Jeanne: This year is going to be amazing. We’ve been talking about taking another hike. I want to hike Washington, but we might do the John Muir Trail or something in California. The snow will be incredible. And much harder to hike.

Articiple: How did you make these patterns on the large wall pieces?

Jeanne: Those are screen printed. Everything in the show except those patterns is hand-painted. I have access to an amazing print shop at Solano and I have people working with me. We did this screen print and I liked it enough to incorporate it.

Articiple: It’s so textural! Can I touch it?

Jeanne: Yeah. It’s really thick. I’m using plastisol, which is like a textile ink. I feel like it blends visually with the other stuff, but I’m interested in making things by hand.

Articiple: And then you painted after you installed?

Jeanne: I used Matt Reynoso’s big, beautiful wooden ladder. There was a night where I just put stuff on the floor in here and got up on the ladder and dripped from the top. I knew I wanted an effect like that.

The piece you saw in Vallejo had drips that I made right on the wall. But this was a little more in my control.

Wild By Nature, 2016

(Collaboration with poet Canyon Steinzig)

Installation, Temple Art Lofts, Vallejo CA

In conjunction with the Visions of the Wild Film & Arts Festival 2016

Articiple: When you deinstall this wall, will this stay in one piece?

Jeanne: No. I was thinking about that. I’ll probably have a box with rolls.

Articiple: Each of these is its own separate piece.

Jeanne: It’s all placed. It’s going to look like nothing when you take it down. But these elements can be recontextualized. I liked the fact that I could come in here—Matt and Lena were so generous in letting me make it as a piece. So I was painting in the exhibition space.

Matt: And you had time, which was nice. There wasn’t a rush. Sometimes it’s like, you have two days to install.

Jeanne: When I’m taking it down, you’re going to be like, get it out of here! It does pull off really easily, though. And my game has gotten cleaner. The wheat paste is much thinner. I could reinstall this pretty easily, I think. This piece [central wall] has been installed three times, in Vermont, at Solano, and then here. It looks different every time, because it’s a different-sized wall. It feels a little different here because it’s missing the whole top section.

It’s acrylic, so it’s waterproof, so it doesn’t damage it to wet it and take it down. The only thing is, this part is my fountain pen ink. For some reason that bleeds a little bit. So I kind of learned a lesson. I like this kind of thing, I embrace the changing mark. But I know that out of all my materials, that ink runs. And it’s not supposed to.

Take: Maybe because it’s on plastic [the pellon substrate].

Jeanne: Maybe my Japanese pen does not like polyester!

Articiple: I like this piece. From this angle the whole piece is like a stele from 2001, like the beginning of writing, the beginning of symbolizing.

Matt: Should we put on monkey suits and jump around?

Articiple: And scream and hit each other with bones. Or should we fast-forward to the part where we all fly away in space ships?

Take: Maybe both!

Articiple: So, this piece was what came out of using the fabric patterns?

Jeanne: This was really influenced by Helen Frankenthaler. I met her when I was in high school, in Milwaukee. I was lucky to have a good art education, so I knew her and her significance. When I went to meet her, I shook her hand and I remember thinking, “Holy cow!” She had these big manicured fingernails. It was crazy. It threw me. I just thought, this is not what I think of from a female painter.

Hiking Helen Frankenthaler Up/Black;

Hiking Helen Frankenthaler Down/Yellow, 2017

Installation view

Acrylic on canvas

Articiple: She was very elegant, right?

Jeanne: She was super glamorous.

I feel lucky that I was able to grow up in Milwaukee in the proximity of an amazing collection that I could see every day. We had this program at the Milwaukee art museum where every day in my high school we would go down there in the afternoon for a class. It was amazing.

Articiple: Milwaukee still has a good art scene. For a city that size, it’s got a lot going on.

So what about these smaller pieces? This piece is folded?

Jeanne: This is a fabric that I made with my fountain pen in my sketchbook. It’s an image of a clear cut forest from above. I used an iphone app and then I sent it to Spoonflower and had them print it onto linen. So it’s a digital print. It’s fabric that I glued down and then painted back into. But I made the mistake of using clear gesso, which caused it to cloud. So I feel like there is work in this show that I’d like to spend more time with.

Articiple: What would you use instead of clear gesso?

Jeanne: Polyvinyl adhesive glue, maybe. It’s for bookbinding.

For this piece, I wanted to see how low-tech I could be, meaning only the digital stuff I could do on the phone. There’s something to be said for limiting your possibilities. When I was hiking I had to learn how to write on my phone. We had some friends on the trail that we really loved, who started hiking with laptops. They were amazing artists, they wanted to document things or be able to upload stuff. After a couple hundred miles they realized that’s too much to carry.

Articiple: Not when you’re living outside. Maybe if you’re staying in a cabin.

Take: Did you have solar panels to charge your phones?

Jeanne: We have an external battery. It’s the size of the phone and it’s fairly heavy. But it will charge your phone for about a week—it charged my phone and Canyon’s phone and Adeline’s Kindle. The only technology we had to charge externally was our spot device. We had a satellite communication device that we had to keep charged.

Take: So that’s to send emergency texts?

Jeanne: Yeah, that’s one of the things it can do. That was really helpful. There’s a button you can push when you need an immediate rescue. If you push it that means they’re going to send someone with a helicopter.

Take: And then you have to pay!

Jeanne: Right. So we encountered a hiker who told us he was dying. He said, “If you have the emergency device, use it!” Because Canyon is an ER nurse, he was able to assess the situation. We were in a place where there was no place to land a helicopter. So with that device, within about 15 minutes I was able to get a Yosemite ranger texting with me. He was asking, “What does it look like? What’s going on? Can you land a helicopter? Can you move him?” It all worked out and it was way better than sending a helicopter.

We were hiking with people who did have to use their device to get their kid rescued. He got a really bad injury in the snow in Washington and they couldn’t walk out. So they sent a horseback rescue.

Articiple: That’s a little better than having to send a helicopter.

Jeanne: In the hiking community there were people who were very judgmental about it. I felt like, you have to do what you have to do.

Articiple: Definitely. If your kid is hurt, why would you put them in more danger?

Jeanne: There’s always the judgment though, like, “Oh, they’re idiots.” That’s not true.

Articiple: Nobody plans to have an emergency. That’s the whole definition of emergency.

Take: How did you caught in a hailstorm?

Jeanne: We had a terrible experience with another artist, because I made a mistake. I wanted more than anything to sleep above the tree line because it’s so beautiful. We were all set up in the dark and we were eating and it was great. Then the storms came in from both ends of the valley. We packed up and ran. Adeline and I ran off the mountain and kept going. We got to the tree line and we were like, “Look at us, we’re so cool. Everything is great.” Then the sky opened up. The hail started coming so fast and so hard, I had never seen anything like it. It was a superstorm! It was incredible.

Within minutes, we were freezing and we didn’t have a shelter up. So we had to put up a shelter quickly. Canyon did that. He got in with a frying pan and dug it out, because it was full of hail. That night, the water was just running under it. I have a cell nylon cover for my sleeping mattress. It wicked all of the moisture. All of the water that was flowing below us went into my sleeping area. I was freezing. I had to get naked and lay on Canyon skin to skin to get warm. Little Adeline was like a pink ball of fluff sleeping in the middle, totally fine, but in the morning Canyon and I were all hung over and sad.

We were at a waterfall where there was hail just flowing by us. It was nuts. We hiked to a ranger station where the ranger had been working there for 40 years. He was in his 70s. He said it was the worst storm he had ever seen. So then we didn’t feel like idiots. It’s just that weather can be crazy. But I’ll never sleep above tree line again.

Take: Did you hike through any place where you were always above tree line for more than a day?

Jeanne: You have to time it right so that you hit it where you can go over the pass and get down to safety. We did have one night where we slept above tree line and it was fine. But if the weather’s bad, you have no place to go. The chance of getting hit by lightning is much higher. Every year there are hikers who die in their tents sleeping up there.

Articiple: I’ve heard about people getting struck on top of Half Dome, even though that’s a really well-monitored area.

Jeanne: There’s a Faraday cage on Mount Whitney because somebody did get hit by lightning in the hut. They have these stone huts that are supposed to protect you from the elements. But a guy was in there in inclement weather and got nailed and died. So now the beautiful hut has this big, crazy metal box around it. You’re not allowed to sleep in Muir hut, on Muir Pass. It’s circular, it’s so beautiful. It looks like a fairy house. But it’s not a safe place to sleep because of lightning.

Articiple: Tell me about these pieces.

Jeanne: Those are me exploring collage, and also playing with some of the patterns I had made. These patterns are the soles of shoes. This is the pattern on the bottom of Vans. This was originally designed as a skateboard deck.

This piece is close to my heart. The athletes that made the protest gesture, the black power salute, at the 1968 Olympics—Tommie Smith and John Carlos—also trained on the PCT. There is a monument to them on the trail. I always like to think that they hatched that idea on the PCT, because it’s a great, expansive space to think about, “What are we going to do?”

A lot of people are out there thinking, “What’s going to happen next in our lives?” I just ran into a woman at the Oakland Museum who we met on the PCT. She said, “After the PCT I had a kid and now I have a whole different life.” Her life completely changed.

Articiple: This is a really important piece in the show. There are still ways that environmentalism, or even the protection of open spaces like the PCT, is seen as separate from social justice issues, as if the way we treat the environment is not connected to racism or violence or other problems. So bringing in this image of Smith and Carlos starts to make some connections between issues.

Jeanne: I’m trying really hard to make those connections. Naomi Klein did such a good job in This Changes Everything, her book about climate change. She brings it to activist culture around the country and around the world. This era that we’re living in, where people feel that the answer is to build a wall and keep everyone out, is really going to make it impossible for us to share resources and live peacefully. It’s going to bring on war and pestilence.

The cool thing for me about the PCT is, it’s a very hopeful space. A lot of the folks who are on it are trying to be their best possible selves. So there is a lot of discussion around social justice. The year we hiked was the year that gay marriage was passed. The kids we were hiking with were so excited and moved by this that they rented a U-Haul and went to the gay pride parade in San Francisco from the PCT. All levels of hilarious mayhem ensued. They got pulled over by the police. Of course it was documented, videod, in the way everything is now. The cops realized that they had this crazy situation where there were 22 people in the U-Haul who were naked and filthy and laying in hammocks. It was just like Facebook candy, we were all following it from afar. The police were laughing when they saw what was happening. They made everybody get out and sit down, and they issued each and every one of them a ticket for not wearing a seatbelt, and then they sent them on their way. So it worked out ok, and they did get to go to the gay pride parade in their U-Haul despite the police intervention.

People on the trail cared about the environment, but also about other people. You could tell when you ran into new hikers, because they would say, “You’re going to love this place, you’re not going to see anyone!” Whenever people said that to me, I thought, actually I’ve been outside long enough that I’m super happy to see other people. Generally the people that I meet on the trail are so cool that I want to meet them. I’m not just going for the solitude. I’m going for community and adventure. Usually an adventure happens with other people.

Articiple: I really like how you’ve taken this in so many directions for the show, starting with natural patterns and forms and making all these permutations.

Jeanne: I’m happy to be in a place where things are very fertile and I can play with ideas. Now I feel like I can circle back to some of these things that I didn’t quite investigate all the way. I think there’s enough here for me to dig into for a while.

Articiple: What direction do you think you’ll go in next?

Jeanne: I’m really interested in working in the landscape. I’ve identified places where I live. There are these old foundations where I’d like to do some very mild intervention and document it. Then I’d like to think about what that is, and try to take it into an urban environment. I think it would be cool to have an unfolding of what’s happening in the landscape, in the watershed, and what’s happening in the city.

There is a lot here that I don’t feel that I completely explored with the social justice angle. I could go further with that.

Articiple: That could be a show in itself.

I also love everything you’ve done with tessellation and pattern variation. I just finished the series using Islamic knot tiles, so I’m thinking a lot about that too.

Jeanne: That’s something I’ve been interested in for a long time. I feel like pattern is about empathy. I think there’s something for humans about wanting to see things that are repeated. It gives you comfort if you’re searching for food, to see repetition. So there are all these ways of conveying that, looking closely and realizing that the patterns in nature are really complicated.

Articiple: And they really signify a lot. There’s so much information there for someone who’s relying on visual perception and pattern recognition for survival. Really it’s like the foundation of thinking. You need repetition to understand relationships, to say, “I saw this before, but that’s new, how does that relate to this?” It’s primordial.

I really think art must have started with abstraction and patterning. Before you’d made a representation, you’d first just be making marks with your hands or your feet. You’d notice marks, and then start making them intentionally, just playing with the mechanics and the visual impact of that.

Take: Like the old cave paintings, hand prints and things like that.

Articiple: Right!

And I love that you put Adeline’s Totoro in the show.

Jeanne: Yes, Totoro made it 2,000 miles. There were other things Adeline carried for awhile. People would give her things, and every now and then we’d have to shake her down and make her send things home. But this made it all the way. It’s very sweet. It’s a forest spirit. It’s very beautiful.

Articiple: Is there anything else in the show that we should talk about?

Jeanne: This piece is a representation of Glen Pass, which is really steep. This is the one actual landscape painting. Very little of this show feels like representational landscape, it’s more emotional or psychological, things that I experienced.

This painting is my attempt to make clear the steepness of the granite. It’s 3,000 feet straight down. It’s terrifying. I’ve been through twice, once in one direction and once in the other. Both times it made me really queasy. I’m really afraid of heights and I’m not a good descender. I find that when I’m up in these places, one reason I like being around people is, it helps make the pass possible. I ran into these wonderful Mormon women who chatted me down off the pass. The whole way, we just chitchatted. It was great, because I could just watch this woman’s feet and think, yeah, I’m watching her feet, it’s cool, I’m not looking down and feeling sick to my stomach.

The worst part was looking over at my child and feeling, oh my god, what if she slips or fumbles. She’s much better than I am in terms of that kind of thing.

Articiple: Not nervous about heights.

Jeanne: No, she’s not. And I’m terrified, so I’m glad to be with people who can handle it.

Articiple: Are these pieces both about Glen Pass?

Jeanne: This one is the hailstorm. It’s about what it felt like when the sky opened up and it was like this biblical deluge. It’s the power of nature, where you realize that you are fucked. I had that thought with my friend Anthony Ryan, who’s an artist. He’s hiked 300 miles with us at least. Every summer he has a near-death experience. This time, I remember feeling like, I got kind of floppy inside, and I literally had the feeling like, I might die tonight. I really thought hypothermia was going to set in and we weren’t going to be able to pull out of it. Luckily, Canyon is not like that. He’s like, “We’re going to deal with this!” He just started working.

Articiple: He’s like, “You’re not bleeding, you’re not having organ failure—“

Jeanne: But the artists were like, “I guess it’s time to die.” It doesn’t say a lot for art. I actually can’t speak for Anthony. All of us were huddled under a blue tarp trying to stay dry. Finally Canyon got it going and dealt with everything. But this piece is how it felt—it was a biblical, epic event.

Articiple: It looks like everything is rushing towards you.

Jeanne: I feel like I’ve drawn this a lot and I’m still trying to figure it out. The other thing is, finding ways to translate sketchbook drawings into bigger pieces is difficult because you have to scale up a mark, and finding the right tool for that is hard. I’m almost there. I don’t totally know what that tool is, but I’m getting closer. In the scale of the show, this gallery is not a big space. Most of the work is fairly small. Most of the things hanging on the walls tend to be head- or shoulder-size. But I love making the big pieces. I want to be in it with my body.

Fantastic Article. Great images.You are so articulate, Jeanne. Great questions Articiple.